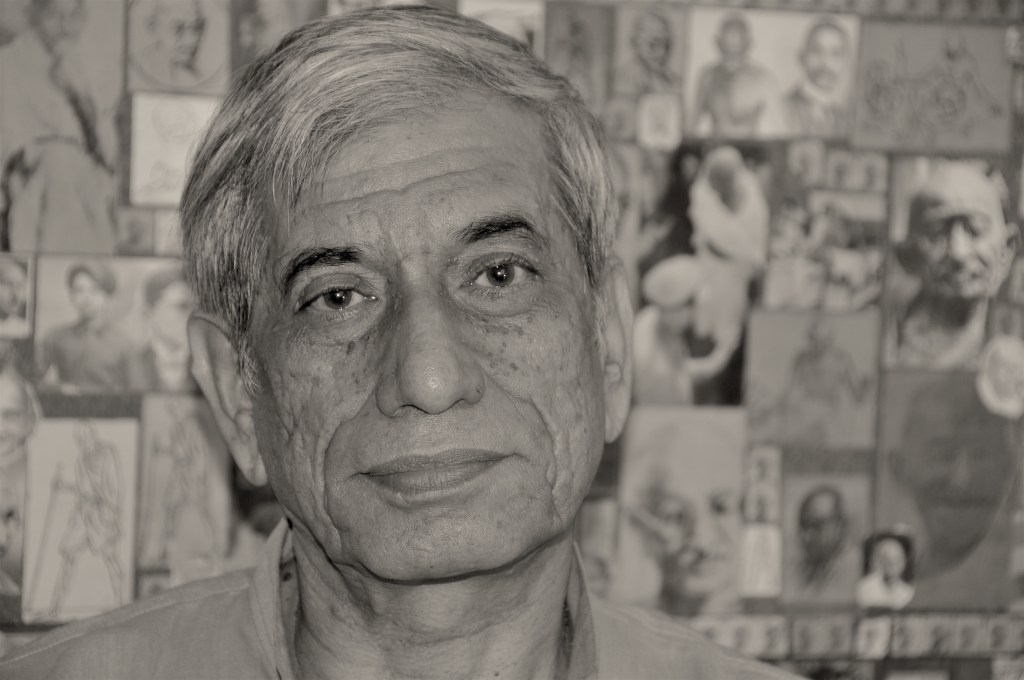

Anupam Mishra – (22 Dec 1947 – 19 Dec 2016)

…

[ This article appeared in the Economic & Political Weekly in its issue dated January 28, 2017.]

Since Anupam Mishra’s death on December 19, 2016, after an 11-month battle with cancer, numerous tributes have been published, several condolence meetings held. Most have dwelt on his personality, more than his work. Not without reason, for his work is now quite well known, especially his bestselling Hindi book Aaj Bhi Khare Hain Talab, first published in 1993. An extraordinary person in several ways, Mishra steadily – actively – managed to avoid attention on his personality. The day Mishra died, journalist Ravish Kumar actually said in his show on the channel NDTV India that he can now talk about the person, and not just his work, since Mishra is not around to deter him any more.

Mishra’s work is inseparable from his life; his personality created his work, his work shaped his persona. He is often described as an environmentalist, although Mishra didn’t like the term; he was averse to new-fangled language or any kind of emphasis on classical/technical learning. His words of choice came from farms and pastures, railway stations and bus terminals, from dialects and sensibilities not often found in learned circles. He called himself a faithful clerk of ordinary people, of ordinary communities.

In 1969, when he started working, ‘environment’ was not a common term, as also its Hindi translation paryavaran. He was a young post-graduate in Sanskrit from the University of Delhi. He had dropped his PhD plan because his professors were not interested in his proposal to make 3D models based on the descriptions in Natyashastra, the ancient Sanskrit treatise on the performing arts.

He was born and brought up in an atmosphere that prized Indian languages and socially relevant work. His father Bhawani Prasad Mishra, a renowned Hindi poet, had learned Persian and Bengali during his incarceration in 1942-45; he was jailed for taking part in the Quit India movement. After his release from prison, he settled in the Mahila Ashram in Wardha, Maharashtra, (very close to the Sevagram where Mohandas K Gandhi lived and worked), along with his wife Sarla and a young family.

Then the family moved, first to Hyderabad and Bemetara (now in Chhattisgarh), and in 1958 to Delhi. In the late-1960s, Mishra’s father was the editor in charge of the Collected Works of Mahatma Gandhi (CWMG) in Hindi. The 22-year-old Mishra joined the Gandhi Peace Foundation (GPF) in 1969 as an apprentice in its research and publications unit. He spent his entire productive life – 47 years – at GPF, politely turning down several lucrative offers from newspapers and well-funded organisations. He treated people at GPF like his family, and he didn’t believe in changing families.

GPF had been created in 1963 for research, publication and advocacy on socially relevant issues. It founders were from the top of the government machinery – Dr. Rajendra Prasad, Dr. Zakir Hussain, Chakravarti Rajagopalachari and Jawaharlal Nehru, among others. Yet they felt the need to create an independent, autonomous body that worked only in the social framework, free from the trappings of governments. Mishra wanted a part of that.

He started as an editorial assistant contributing to Gandhian communications channels such as Sarvodaya Press Service and Bhoodhan Yagya, honing his skills as a writer, editor and photographer. When the Gandhian leader Jayaprakash Narayan engaged with dacoits in the Chambal valley to persuade them to surrender, his three-member team on the ground in 1972-74 included Anupam Mishra. After the dacoits surrendered, GPF brought out a book titled Chambal Ki Bandookein Gandhi Ke Charnon Mein. Veteran journalist B.G. Verghese had called it “the fastest journalism in India”.

It was around this time that Mishra’s attention turned from the Chambal ravines to the Himalaya, towards ordinary villagers protesting commercial logging in the higher reaches of Chamoli district of Uttar Pradesh (now in Uttarakhand). In October 1972, at the Gandhi Samadhi in Delhi, he met Chandiprasad Bhatt, a Sarvodaya activist from Gopeshwar. Mishra took him to meet Raghuveer Sahay, the editor of the influential Hindi magazine Dinman. This resulted in a special issue on this mountainous region, which talked about the struggles of villagers in the face of loggers and the forest department.

From 1973 onwards, Mishra began travelling to some of the villages in the region. Not like a journalist from Delhi, but as a sympathetic ear. Wherever he went, he stayed for a few days to understand the villagers, their hopes and fears. It was much later that Mishra wrote a feature article in Dinman. It was perhaps the first major report by a journalist from outside the hills on what later came to be known as the Chipko movement; it was published along with the famous photograph of Gaura Devi, a protagonist of Chipko.

Along with Satyendra Tripathi, Mishra wrote a book in 1977 on the Chipko movement that was to herald a new environmental consciousness. Historian and writer Shekhar Pathak calls Mishra the first historian of Chipko. But Mishra never saw himself as either a journalist or a historian or a photographer or an environmentalist; rather a faithful messenger for the villagers and the activists, as their man Friday in Delhi. He readily assisted Bhatt in his work and became an associate and guide to other journalists and researchers writing on Chipko.

During the Emergency, Mishra worked as a freelance reporter and photographer, often alongside other journalists protesting the government’s excesses. GPF had emerged as the hub of anti-Emergency activities, and Mishra did his bit.

Around the same time, he began travelling to the Narmada river basin, not far from his father’s ancestral village. Irrigation canals from the Tawa dam had caused waterlogging in the otherwise fertile fields with black cotton soil. When villagers joined hands against the ill-effects of the dam and its canals, it became the Mitti Bachao Andolan, also the title of a thin book Mishra wrote on the struggle. Again, Mishra was not just the first chronicler and messenger for the villagers, he was their friend and associate. Later, this movement segued into a wider protest against dams in the valley.

The early-1980s drew Mishra to Bikaner in western Rajasthan, where social activists were rallying to protect common pastures. He made friends there, brought journalists from Bikaner to Delhi, and took journalists from Delhi to Bikaner. (One of his favourite words was saakav, which in western Maharashtra means a small, seasonal bridge; Mishra saw himself as a saakav.) It was during these travels that the wisdom of thedesert folk and their traditional water management came to his notice. Over the past decade, he had observed how ordinary people related to their physical environment. How their practices and lifestyles were shaped by the physical conditions, and how they in turn shaped their physical conditions. They had not learnt this through a classical education, nor through modern learning; it was common sense, accumulated over generations, transferred in the oral traditions.

Mishra had lots of affection towards all kinds of people he met during his work and travels, and he made it a point to stay in touch with them, to foster the relationships, through good times and bad. He wrote numerous postcards by hand and called people regularly, a habit he had acquired from his father, a generous man with a charming manner that made each person who met him feel special. Mishra was no networker, he simply kept expanding the range of his home and his family ever further. His office in GPF gradually became a source of great recourse to all manner of people, who came there just to meet him. He always found time for each person who came to meet him.

Among his regular visitors were a few mentally disturbed people, who had been cast aside by their near and dear ones. One of them, a schizophrenic, didn’t trust anybody other than Mishra. He appeared regularly at the office, and Mishra used to leave aside all work and step outside to meet him, hear him patiently, help him in some small way, come back to his seat, and remind other visitors that mental imbalance is a lottery; any of us can lose our mental balance at any time. Among his favourite works of fiction was Anton Chekhov’s Ward No. 6. Mishra had compassion even for colleagues who mistreated him. Since his death, obituary after endearing obituary has mentioned his remarkable composure and social warmth. On meeting him first, some people suspected his humility was affected. Those who knew his family recognised its origin: his mother Sarla. Mishra had been raised by a devout mother who offered compassion and reassurance to strangers even.

Mishra often talked of how we can get carried away with what we know, and make assumptions about what we don’t know. He stressed the need to be forthright about what we do not know, and to acknowledge the limits of our knowledge. After he relaunched GPF’s Hindi bi-monthly magazine Gandhi Marg in 2006, he often published articles that dealt with the humility required to handle knowledge, be it the views of Vinoba Bhave or a modern scientist like Stuart Firestein. The magazine steadily grew under his editorship and acquired a committed readership.

His personal qualities characterised his work. There are others who researched and wrote about traditional water management in India with great depth and commitment. Mishra, however, saw himself as the voice of his people, his society. He did not see with the eyes of academic objectivity or impartial commentary, but with empathy and imagination. His discerning editorial taste meant he allowed his readers plenty of room for doubt, just as he was forthright about the limits of his knowledge. He noticed the environmental wisdom in the ways of ordinary people, he saw the cultural threads and values that carried that wisdom from generation to illiterate generation.

His writing did not alarm; there were no rallying cries, his tone was always understated. With a quiet dignity, his prose showed how to respect the ordinary and the powerless, as also the folly of judging people and things we don’t understand. His criticism was laced with wit, although tempered with a friendly warmth. When he was asked to comment on the proposal to interlink rivers, in which political leader Suresh Prabhu was involved, he said in Hindi: “Nadiyan todhna aur jodhna prabhu ka kaam hai, ise Suresh Prabhu na karein” (It is up to prabhu/god to join or separate rivers, Suresh Prabhu best leave it alone).

He produced crisp, vivid text; all his books are slender, because his editing pencil was carved out of Ockham’s razor. No tome, no compendium. He wrote only in Hindi, not out of any ideological obduracy, but because it was the language in which he had grown up, the language in which his friends and subjects were comfortable. His Hindi was steeped in an earthy idiom, his narratorial voice was that of a friend being candid over an evening walk. Yet literary critics fawn over the lucidity, simplicity and attractiveness of his Hindi prose.

Which meant the environmental good sense he described appealed to ordinary people, urged on their imagination. Sachhidanand Bharati, a school teacher in a village of Pauri-Garhwal, Uttarakhand, found in Mishra’s book a description of traditional structures that captured runoff in the mountains, preventing erosion and improving soil moisture. These were called khal and chal. As a young man, Bharati had taken part in the Chipko movement, but he could find no examples of these structures in his region, even if his own village’s name – Ufrainkhal – indicated the traditional waterbodies. Mishra had kept in touch with him over the years, so he asked the writer how to revive these structures. Mishra did not hand him a recipe for a solution, for he was averse to the prescriptive mode; instead, he urged Bharati to talk to old, experienced people in his region. And to experiment with the ideas on his own.

Gradually, along with ordinary village women – the menfolk from these parts usually migrate to the plains in search of employment – Bharati and his associates built scores of such traditional structures. Today, the health of hundreds of hectares of forests in the region owes to the revival of these structures by ordinary village women. They have an abundance of fodder for their livestock, irrigation for crops, and the moist forests are less vulnerable to forest fires. Bharati credits Mishra for this, acknowledging the latter’s gentle, wise stewardship.

Likewise, in the parched regions of western Rajasthan, a peculiar kind of well was built traditionally in areas that had a belt of gypsum running underneath. This narrow well, called kui, taps rainwater trapped in the sand. The droplets percolate slowly towards the well, but the impermeable layer of gypsum keeps them from sinking into the saline groundwater. This marvel of engineering had become a thing of the past, and was described by some as a dead tradition, since nobody was making new kuis.

After reading in Mishra’s book a description of how the kui was built, an organisation called Sambhaav has built about 200 new kuis. While these are based on the same concept as before, they have been built with new material – reinforced cement concrete. In Madhya Pradesh, Uttar Pradesh and Rajasthan, ordinary farmers in some regions have revived their waterbodies after reading about it in Mishra’s book, Aaj Bhi Khare Hain Talab. He often stressed that ordinary people have an intrinsic technical knowhow, without which they could not have survived. Just that this knowhow exists in a cultural idiom. If you develop a taste for that idiom, you can access that knowhow.

Apart from how it iswritten, the influence of this book has a lot to do with the fact that Mishra did not employ copyright. Several people published their own editions of the book, either for free distribution or for sale. It has been translated into several Indian languages by enthusiastic readers, who felt compelled to move forward the message of folk wisdom. It’s been translated into Braille, French and English, and an Arabic translation is in the works. The book has been serialised by several publications and radio stations.

How did he manage to finance his efforts, then? For one, he kept down costs. Most of his work was accomplished on shoestring budgets. His commitment and manner encouraged generosity in other people, so there was always enough to get the job done. In his personal life, Mishra lived frugally, just like he had been brought up.

He often said an important lesson he learnt was from his father’s friend Banwarilal Choudhary, an influential figure and an agriculture scientist who had led the ‘Mitti Bachao Andolan’ in the early ’70s. He had told a young Mishra that good work does not depend on a wealth of resources. That an abundance of resources becomes a preoccupation and a distraction from the overall objective. Mishra took this lesson to heart and made it the cornerstone of all his efforts over almost five decades.

On his chair in GPF is an anti-dam sticker from the 1980s. Power Without Purpose, it says. It is a reminder that Anupam Mishra believed only in the power of purpose. In the genius of the ordinary.

– Sopan Joshi

Categories: Media

अपनी खूंटी पर टिका, एक सुनने वाला पत्रकार

अपनी खूंटी पर टिका, एक सुनने वाला पत्रकार  Media is the message. Live debate is the story

Media is the message. Live debate is the story  Part 1: The Coordinator of Our Daily Maladies

Part 1: The Coordinator of Our Daily Maladies  भवानी प्रसाद मिश्र: हम जैसा बोलने वाला एक कवि

भवानी प्रसाद मिश्र: हम जैसा बोलने वाला एक कवि

🙏🏽

>

excellent description of an excellent person

Respect and fond memories of a gentle and wise man.