…

In the rarefied air of Tibet lies a transcendental

experience on two wheels.

An account of Royal Enfield’s Tour of Tibet 2014.

Text and photos by SOPAN JOSHI

…

[ An edited version of this article was published in the March 2015 issue of Outlook Traveller ]

…..

It was the first day of Royal Enfield’s Tour of Tibet 2014. I was sure it was going to be the last day. Standing on the back of a truck, overlooking the driver’s cabin, watching the truck’s right front wheel teetering inches from the edge of a near-vertical slope of hundreds of feet, falling away into a snaking river, I was readying to shuffle off the mortal coil. There were other dangers, too.

Behind us were the motorcycles we had loaded on the 4×4 truck; three trucks for 16 bikes. They were flung from side to side as the driver manoeuvred the truck over—and around—pieces of the Himalaya obstructing the path. Worried about the damage to the vehicles, I tried to hold on to them as they rolled back on the uphill climb, imperiling those standing at the rear of the truck. When the truck hit a downhill patch, the motorcycles lunged forth in the general direction of my chassis.

The only distraction were the heavy branches hanging down from the trees bordering the path, waiting to viciously bruise those too busy looking down to contemplate matters existential. Avoiding buffets from the boughs required concentration. “Bend your knees,” I repeated to myself, “duck and dive.” For it was getting dark and the truck’s headlights were aimed at the road ahead; the vicarious overhanging vegetation was barely discernible. The late-afternoon downpour, typical of the monsoon in this part of Nepal, had kept its promise and drenched us. Waters from the Southern Hemisphere, transported all the way across the Equator by monsoon winds, were now moistening the inner-most reaches of my skin.

A sound beginning

Occasionally, when the non-road eased into a smoother patch for a few seconds—and when there were no threatening branches or storm clouds above and no chasms to stare at below—my mind wandered to the memory of the last meal I had had several hours ago, on a balmy morning in Kathmandu. On that now-distant morning, we knew that heavy rains, landslides and floods in the Sindhupalchowk district had washed away a section of the road from Kathmandu to the Tibet border in Kodari. We knew it was a choice between riding rough or cancelling the trip.

The tour organisers sent out scouts, who reported that a kuchha path, skirting over and around the hill battered by the landslide, was adequate for motorcycles. A group of motorcyclists had taken that path two days ago and gotten across without incident. Which is why we left Kathmandu after an early breakfast. It had been a lovely ride out of Kathmandu. The road was firm, the weather clement. Before launching into the hill path of our tour’s redemption, we had stopped for refreshments at a small town. It was just before noon; some of the riders had snacks, others had lunch. I passed; I prefer an empty stomach when riding over rough surfaces.

The first stretch of the unmetalled path was entertaining: firm track underneath, laden with loose rocks and pebbles. Gradually, the climb became increasingly vertical. Unfortunately for us, some adventurous truck drivers had discovered that path. Their heavy wheels had gnawed away whatever little traction the path afforded, opening the surface to rainwater. This meant the sections between rocky patches were full of slush and loose mud.

Now don’t get me wrong: I love off-roading. The challenge of a bad surface appeals to me, it makes things interesting. But I need an enabling vehicle. Here, my ride was a Continental GT. Its forward-swept riding position and sticky road tyres are ideal for cafe racing in the urban jungle. It is exactly what should be avoided on an unmetalled Himalayan road molested by the monsoon and 4×4 trucks. Off-road or dual-sports motorcycles have an upright riding position that allows the rider to stand on the footpegs through rough roads, with the knees absorbing the shocks. They also have knobby tyres for extra grip in the slush. My GT—Grand Tourer, if you please—was skidding and struggling for a hold. I was struggling harder.

A test of physical fitness

The afternoon sun was hot. We were all wearing full riding gear, which made it hotter on the inside than outside. And then there was the adrenaline from negotiating the bike over a moonscape—off-roading is very demanding of the body, and good off-road riders are very fit, athletic people. Not like me. In the interests of full disclosure, I had begun physical training just three weeks before the tour. Clearly, it had not been enough.

My heart pounded so hard I could hear it over the engine revs. Inside the helmet, my head was steaming. As I straightened my arm, sweat dripped down the sleeve of my riding jacket in a steady, if thin, stream. I needed to stop every 100 metres or so to regain my breath. I realised most everybody else was struggling just as hard, sprawling out on the rocky surface to stave off exhaustion.

Then it got worse. We hit a terribly slushy, vertical stretch. Everybody was stuck now, not just those of us who were unfit of body and short on riding technique. At this point, the 4×4 trucks were hired to take us and our motorcycles over the rough patch. The terrain that looked impossible to us was regulation territory for the truck drivers. They were going very slowly, using spotters to guide them through the dangerous patches. When I was alert to what our driver was doing, I felt safe. I could have learnt a few off-road driving tips and tricks watching him, if I weren’t so paranoid.

By about 7pm we had crossed the highest point of that path and begun the descent. After about an hour we hit a traffic jam. A truck had broken down on the single-lane kuchha road, and it was going to take a few hours to fix it. Now, the only choice for us was to walk down the hill for about four kilometres to the road, where a bus was waiting for us. Before we set off on foot, Lucose, a rider from Singapore, brought out chocolates and energy bars for everybody. That fuel was critical, because the trek down took more than four hours—not to mention blood, sweat and tears. Because most of us wore riding shoes designed to grip tarmac (like the tyres of the GT). Going downhill on the mud and water of a hill path, they felt like skis.

R&R, for body and bike

It was only around 2am that we reached the Last Resort near Kodari, where food and comfort awaited us, after a remarkably tough day. The trucks with the bikes arrived a few hours later, with the bikes looking badly damaged; our Tour of Tibet appeared doomed. Some of the riders were quite upset with the organisers for putting them through such an ordeal. The organisers said they had never faced anything remotely similar, so there was no way they could have prepared for it. (As for me, I know the Himalayan region is capricious, especially during the monsoon. Having been stuck for days altogether in the mountains on a few occasions, I approach the greatest wall in the world with humility: no matter how well prepared you are, there is no telling what the Himalaya might spring on you.)

We spent the next day recuperating, getting massages at the spa, intermittently watching the mechanics restore our bikes to working order; the support truck trailing us was carrying spare parts. On the third morning of our ride, 14 riders and a support truck took off for the Sino-Nepalese Friendship Bridge, which has to be crossed on foot, dragging the bike along, switching from the left side of the road to the right side.

Border formalities took half a day, primarily because the Chinese customs took their time inspecting the vehicles. We met our guide Tenzin, who kept warning us to not take any pictures in that area—this was our first brush with the Chinese authorities, and we would later become accustomed to a check-post every 30-50km. If not the army, then the customs or the local police.

Chinese roadbuilding, though, is another story. From the bridge to the border town of Zhangmu, the road was firm and cemented. The climb was very vertical here. From Kathmandu (altitude: 1,200 metres) to Kodari, we had gained 1,300 metres in 115-km stretch. From Zhangmu to the town of Nyalam, where we were going to stay, we gained 1,450m in altitude in a matter of 33km.

But what a 33km it was! The road was smooth, the scenery uplifting. Irked by the lack of mobility over the past two days—landslides, bad roads, immigration—I charged ahead. It was just the kind of surface the GT loves, so I played with the throttle. But the truck ride had taken a toll of the front wheel’s alignment. I felt a wobble in a high-speed corner, inducing a heart-in-the-mouth moment. After that, I slowed down and focused on the scenery. Only to realise that in the rush of speed, I had failed to notice when I had gone above the treeline.

Elevation!

We were in Tibet now. Sparse, shrub-like vegetation. Cold winds, especially in the morning and evening. A heavy head due to the lower oxygen pressure at high altitude. And scenery so dramatic it dwarfs everything else. It is possible to see for miles and miles in any direction (without needing the assistance of any uplifting substance). All pleasure and pain, all sense of failure and success, all thought and sensory perception—even the sense of self—disappears when nothing is in your face.

How many times can you look around and let out a sigh? After a while, the ruts of the mind accept that this world is real; that when you wake up in the morning, the view will still be around. It takes only an instant, however, to realise why this land is constantly linked to meditation—and a certain philosophical distance. The kind of views that end all conversation and breed silences that take meaning out of meaning. The Dalai Lama’s beatific calm does not result from his exile, I promise you; it is an imprint of the Tibetan landscape.

I thought I understood the meaning of the term ‘perspective’. Everywhere you turn, there is a photo-op. Yet there is not an eye or a lens that can capture it. Perhaps the view meant that much more because of the difficulty we faced in getting there. But the moment we climbed the plateau, every single one of us had forgotten the travails of the past two days; the struggle to ride up the kuchha hill path, the adventure of the 4×4 truck, the exhausting trek, the sight of the smashed-up bikes after the truck arrived at Kodari…everything seemed like a news-item-in-brief in yesterday’s newspaper.

The next day we rode up to our first mountain pass; at 5,150m, Thong La offers stunning views of the Himalaya, including Tibet’s highest mountain peak, Shishapangma, the world’s 14th highest at 8,027m (and the shortest of the 14 ‘eight-thousanders’). Riding down the pass’s rapid northern descent, I had my first taste of altitude sickness. My head felt woozy, disoriented. I had but myself to blame, for missing breakfast in the morning after waking up late. At Old Tingri town, I had a sumptuous lunch, and took seriously all meals thereafter, tucking in with a sense of purpose. We covered 240km, stopping at New Tingri town at an altitude of 4,300m.

Having lost a day to the landslide, we did not have the time to stop anywhere for an extra day or visit monastries like Sakya, which was a detour on the route to Shigatse, Tibet’s second-largest city, where we reached the following day after another 240-odd kilometres. On the way we crossed two mountain passes: Gyatso La (at 5,248m, Tibet’s highest pass) and Tso La (4,750m). On the last stretch to Shigatse, the highway swung by villages. September is Tibet’s only harvest season, so villagers were out in full strength.

Along came a cow…er…donkey, actually

Going through one such village, I saw some of our riders talking to villagers. Aakash of Royal Enfield was waving me on, gesturing me to not stop, so I didn’t. I heard the story after reaching Shigatse. Our guide Tenzin had warned us over and over to go through populated areas very slowly. Arnav—at 18, our youngest rider, who had got his driving licence a few weeks ago—collided with a cow at a fair speed. That’s what he thought, at least. Later, it turned out to be a donkey.

Tony Kierath, a surgeon from Perth in Australia, the oldest and fittest rider in our group, examined the donkey and declared him fit. But the villagers would have none of it. They had to be placated with a payment of RMB 500. Arnav suffered only a few bruises, thanks to the safety gear he was wearing. His motorcycle, though, had to be loaded on to the support truck.

At the briefing the next morning—yes, each day’s ride began and ended with a briefing—Tenzin related to the group an accident that had happened the previous year, on the first Tour of Tibet in 2013. It had resulted in fractures, hospitalisation, and terrible inconvenience all around. After Arnav’s donkey incident, Tenzin and his boss Rabi Thapa, along with Sachin and Aakash of the RE Rides Team, insisted on everybody riding slow and with great caution. Arnav’s bike was fixed that evening itself. He was buoyant, entertaining all of us with his youthful energy—and the butt of many a donkey jokes for the rest of the tour.

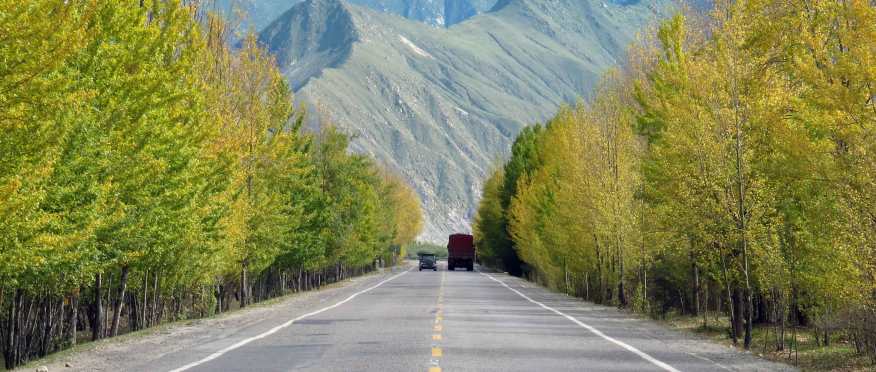

The road to Lhasa from Shigatse has severe speed controls, enforced rigorously by the police. The road is quite narrow and treacherous in patches. At one spot, the authorities have raised a crashed car on a plinth as a warning to speed devils. For extended stretches, this highway runs alongside the Yarlung Tsangpo river, known as the Brahmaputra after it enters India. This is also the route for the recently completed railway track between the two largest Tibetan cities, a controversial engineering marvel that awaits commissioning. About 70km ahead of the Tibetan capital, we left the Tsangpo valley and turned north, riding along one of its tributaries, the Lhasa river. Reaching Lhasa felt like one of life’s great achievements, primarily because of the pressure to ride slowly on the last day, for fear of another accident.

Lhasa, which we explored on our one free day, was a study in cultural contrast. To the east lie the Potala palace and the Jokhang temple, the heartbeat of old Tibet. Here, you see the devout undertaking great pains in their spiritual praxis. The palace alone is well worth the visit. The architecture of this part of town is old, and one feels transported back in time. Western Lhasa is all steel-and-glass modernity, populated by Han Chinese.

By now, everybody had acclimatised—even the one person who had such a bout of altitude sickness, he could not ride (his bike came in the support truck). The off-day was as much enjoyment and shopping as rest and recuperation. On the eight day of our tour, we started back, via a different route. We were headed for the historic trading town of Gyantse. This was the best ride of the tour, not just for me but for most of the riders as well. We climbed up to Gampa La (4,800m) and were treated to the magical sight of the blue Yamdrok lake on the other side of the pass.

The ride of my life

Our route took us along the lake, a turquoise-coloured dreamscape. We turned away from the lake, climbing to Karo La (5,050m), where the highway runs right under the glacier. The road to the next pass, Sime La (4,300m), was the best stretch for me. Virtually no traffic. Twisty roads, followed by straights, followed by twisties. Smooth tarmac, that eased into a very wide valley with views matched only by the Yamdrok lake on the entire ride. I can safely say the day’s riding was the best I’ve experienced.

It was a petrolhead’s dream, a setting straight out of a James Bond flick. With few villages and no police checkposts, I rode at speeds I shall not reveal here. We went past a spectacular dam. A little before Gyantse, late in the afternoon, thunder clouds gathered, revealing how the spectacular views in Tibet can turn even more dramatic in a matter of minutes. This is the only stretch in Tibet where we encountered rain. It was followed by a wonderful meal at Tashi hotel, run by Nepalese. For people missing food from home, it was a godsend.

Cho Oyu, the world’s sixth highest mountain at 8,201m, is a neighbour of Mount Everest, which was wrapped in clouds

From Gyantse to New Tingri, via Shigatse, was our longest ride of the trip: 330km. It took us through some well populated regions (by Tibetan standards), so we were back to riding cautiously. The next day we set off for Zhangmu, aiming to get the border formalities rolling that evening itself. On the ride down to Zhangmu, we stopped near Old Tingri for a view of Mount Everest, but it was covered in clouds. We did see Cho Oyu (8,201m, the world’s sixth highest mountain). We also stopped at Thong La for our last view of the mighty Himalaya, as seen only from the heights of Tibetan passes.

On the ride down to Zhamgmu, I was right behind Hide Okamoto. He’d raced superbikes before retiring into consultancy for tyre companies. Ahead of him, leading the pack, rode Sachin Chavan, director of the Rides & Community Team of Royal Enfield. The two of them were saddle-sparring, testing each other’s skills. I was best placed to witness the thrilling contest: two skilful riders competing, but restraining themselves to avoid unnecessary risks. I was so engrossed in watching them, that I again failed to notice when we descended to the treeline. By the time I disengaged and turned my attention to the scenery, we were already in thickly wooded hills, with the Tibetan landscape left behind in the wake of exhaust fumes. It was a sad moment, eased only by the waterfalls and the hundred shades of Himalayan greenery. We reached Zhangmu in time to initiate paperwork for the border crossing.

Which meant the Chinese customs and immigration processed us very quickly next morning. After dragging my motorcycle across the Friendship Bridge, I let out a relieved sigh. Nepal felt like home after nine days in a police state. While the Nepalese customs processed our papers, we ate daal-chawal and played pool at a roadside joint. The army had been working on the stretch across the landslide; they had carved a kuccha path through the shattered hillside. It was difficult riding through rocks and mud and slush but all of us negotiated it reasonably well, the experience of the first day standing us in good stead—as it will for the rest of our lives. By the time we got across, it was late afternoon. The ride down to Kathmandu was wet, as we met with a cloudburst. I was the second rider to reach the hotel, by around 8pm. The post-tour celebration was at Handlebar, a hangout run by motorcycling enthusiasts.

I’ve never been fond of riding in groups; I’ve struggled to find people with a matching approach to motorcycles and the road. This tour was the first ride on which I found myself connecting with virtually all my fellow riders. Perhaps the level of difficulty and the commitment required engendered a mutual respect that glossed over the differences. The 18-year-old Arnav from Delhi felt just as much a riding buddy as the 57-year-old Tony from Perth. The friendships forged on this tour will be lasting. Add that to the out-of-the-world sensory experience that is Tibet, and you have the kind of ride that amends your ideas of who and what you are.

Many people ask me about the ride, about the experience of Tibet, the mysterious roof of the world. I feel like an ancient mariner, regaling them with fascinating accounts of the unknown. My Tour of Tibet 2014 T-shirt elicits respect and awe at motorcyclists’ conclaves. Because hey, which serious motorcyclist hasn’t fantasised about, yearned and hankered for that ride through Tibet? Will you be on the Tour of Tibet 2015?

INFORMATION

Royal Enfield’s Tour of Tibet is open to all RE motorcycle owners. The difficulty associated with riding to Tibet—physical, technical and administrative—make it one of the most exclusive routes for avid motorcyclists. It is physically demanding and requires planning and preparation, much in advance.

It is important to remember that RE is a motorcycle manufacturer, not a tour operator. Its Rides and Community team is not a corporate, bottomline-driven outfit. It is more about community and cooperation, less about the corporation. The logistics in Nepal and Tibet are handled by RE’s Nepalese partner, Sacred Summits, a group of RE enthusiasts.

RE held the first Tibet tour in October 2013. It is a very cold month in that part of the world. So the second tour was held in September, which risked the monsoon. Riding to Tibet is trade-off between a harsh winter and monsoonal caprices. Keep an eye out for the dates for the 2015 tour on the Rides section of the company’s website.

COST

Rs. 1,50,000 has to be sent as a demand draft drawn in the name of ‘Eicher Motors Ltd’, payable at Chennai, along with other required documents. (Cancellations a month before the ride are entitled to a 50% refund.) This covers a basic hotel room on twin sharing, bed-and-breakfast basis. Lhasa, Shigatse and Gyantse offer three-star hotels. Hotels at other locations have more basic amenities. Once on the road, each rider is expected to pay for his/her fuel and lunch, which averages to about RMB 200 per person per day.

ARRANGEMENTS

Each rider is expected to ship their motorcycles to Lucknow on an appointed date in August, from where RE arranges their shipping to Kathmandu. Here, the motorcycle is inspected for withstanding the rigours of the tour. A support truck trails the riders and carries the luggage and spares, along with a trained mechanic, all through the tour. An SUV with the guide and organisers moves in front of the riders to smoothen the paperwork at the numerous check-posts, as also to guide the riders. After the ride, RE ships the motorcycles back to Lucknow, from where owners have to arrange their transport. NOTE: We were not required to obtain an International Driving Permit, but do check the details on the website.

FOOD

It makes sense to carry some snacks and water on the motorcycle. In the smaller places, the organisers make food arrangements, which is a limited-menu buffet. Larger cities and towns offer a greater food variety, so the riders are free to go to a place of their choice. Certain places in Tibet can be difficult for vegetarians, so look out for outfits run by Nepalese operators, which offer food that will appear more familiar to Indians. For those who wish to play it safe, most towns have shops selling quality fruits from eastern China.

PHYSICAL FITNESS

Motorcycling to difficult locations is an adventure sport, whther or not it is recognised as that. Which means it makes difficult demands on a participant’s fitness. If a motorcycle falls down, for example, a rider requires strength to lift it up. Riding for several hours requires resilience and muscle strength. RE insists on riders building their strength and stamina a few months before setting off. Fitness is checked in Kathmandu: each participant is required to complete 50 push-ups and run five kilometres in under one hour.

ALTITUDE SICKNESS

The average elevation in Tibet is 4,500 metres above mean sea level. Atmospheric pressure is much lower up there, which prevents a ready infusion of oxygen into the blood vessels inside the lung. This can play several tricks with a person’s health, physically and mentally. It helps if you have some experience of high-altitude locations, although there is no rule on who is affected by altitude sickness and who is spared. In general, a fit person copes better with the difficulty. The support truck carries a range of medicines and oxygen cylinders for an emergency.

SAFETY EQUIPMENT

There are two kinds of motorcycle riders: those who have tumbled off a motorcycle and those who are about to tumble. Safety equipment is critical for surviving the falls. A good, full-face helmet that fits snugly on the head (and doesn’t move independent of the head) is a must. The visor—this is essential—must be free of scratches. For riding gear such as gloves, jackets and shoes, leather is the best material. Gloves are best with reinforcement for knuckles and fingers. Long-sleeved gloves prevent the cold winds from getting inside your jacket sleeve, besides protect the wrist and the lower forearm. Riding jackets must have padding for the back, elbows and shoulders. Riding pants should have extra protection for the knees and thighs. People who don’t like to use riding pants must wear knee-and-shin guards over a thick pair of pants, like jeans. Good riding shoes higher than the ankle, with reinforced outsides, are a must. The higher the better.

Safety equipment is uncomfortable most of the time. Which is why it makes sense to bring slightly used gear, which sits a little more comfortably than crisp, new material. Either carry a raincoat and rainpants to wear on top of riding jacket and pants, or look for waterproof products (remember: nothing is completely waterproof). Several companies now sell riding safety gear in India; these companies are mostly located in Bangalore, Pune, Chennai and Hyderabad, but they supply across the country. Try Zeus, Cramster, DSG or Moto Adda.

Being a centre of mountaineering and adventure sports, Kathmandu is a great place to buy both high-quality and cheap gear for protection from wind and cold. Try the Thamel market.

Categories: Automobiles, Travel

Wheels Of Change

Wheels Of Change  RAJASTHAN: Crash Course in Dune School

RAJASTHAN: Crash Course in Dune School  The automobile is 125 years old

The automobile is 125 years old

Awed. And proud.

During our last trip in the Himalayas our vehicle got stuck in ziddi mud on way to the Zanskar valley in a dip soon after the Drang-Drung glacier. Besides a trucker friend of our driver we were helped by a team of bikers from Punjab and a lone biker from Delhi (originally from Bangalore). We would have been utterly marooned had they not stopped and muddied their gear besides offering sage advice. But for a few drops of kahwa from our flask and silent prayers for their onward journey, we could be of no consequence to them.

Salutes to you and your ilk my dear boy!

नौजवानी की कहानी

This is most daring. I have just vertically scanned the text and found it fascinating. I have kept a copy, will read again thoroughly and respond. Thanks for sharing.

Enthralling!!!